3 Evidence-informed Strategies you should use more often

Learning random teaching tips won't help you as much as understanding key concepts from the Science of Learning

Look, I'll be completely honest with you. Learning lists of techniques and strategies on how to teach more effectively doesn’t always work well. In fact, in today’s world, it seems like this kind of content is exactly what catches our attention. We want something that can be used immediately, preferably in the next class, and that delivers positive results. That’s why what I’m about to share in this article might sound hypocritical — after all, I’m writing a list of useful teaching strategies. However, I believe that if you take a deeper look at what I’m sharing, you’ll realize that more than just simple strategies, what you’ll find ahead should be the foundation of how you plan and deliver your lessons. They can (and should) even be applied to your own learning experiences.

In other words, focus on the general principle behind each strategy and start using them systematically.

DISCLAIMER: The reason why the title of this post uses “evidence-informed” rather than “evidence-based” is crucial. While the two expressions may seem quite similar to you, there's a key distinction that matters deeply for educators and families. Evidence-based usually implies strict adherence to the most current and rigorously tested research, often leaving little room for context or personal experience. On the other hand, evidence-informed means using high-quality research as a foundation, but also drawing on your professional judgment and real-world experience to guide decisions. I normally joke that if a neuroscientist tells you to adopt a certain strategy because it aligns with how the brain learns, ask if they’ve ever actually taught a group of 5th graders. If the answer is no, you might want to take their advice with a grain of salt. Research is essential, but so is classroom wisdom. And evidence changes / gets updated.

STRATEGY 1 – Pretesting

Think about it for a minute. What’s the first thing you do in your class? After taking attendance, of course (does anyone even do that nowadays?). Do you share the lesson objectives, correct the homework, tell everyone to open their books to page 17, and start exercise 2b? Now, imagine starting your lesson with something extra.

The Science of Learning suggests that applying a pretest at the beginning of the lesson is directly linked to students’ performance. What does this mean? A quick test or quiz on the content we are about to teach not only increases students’ awareness but also sparks their curiosity. It also helps retrieve their prior knowledge, and it serves as a great priming strategy — that is, the process by which prior exposure to certain stimuli influences students' responses to new stimuli or information.

Too much? Feeling overwhelmed? Think of it this way. The beginning of a lesson should be like a combination of mise en place in a restaurant and a game show, like Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

Everything set up in its proper place for everyone, with a pinch of excitement about what’s coming next to create the right atmosphere.

Read more:

Little, J. L., & Bjork, E. L. (2016). Multiple-choice pretesting potentiates learning of related information. Memory & cognition, 44(7), 1085–1101. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-016-0621-z

Richland, L.E., Kornell, N., & Kao, S.L. (2009). The pretesting effect: Do unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15(3), 243-257

STRATEGY 2 – Retrieval Practice

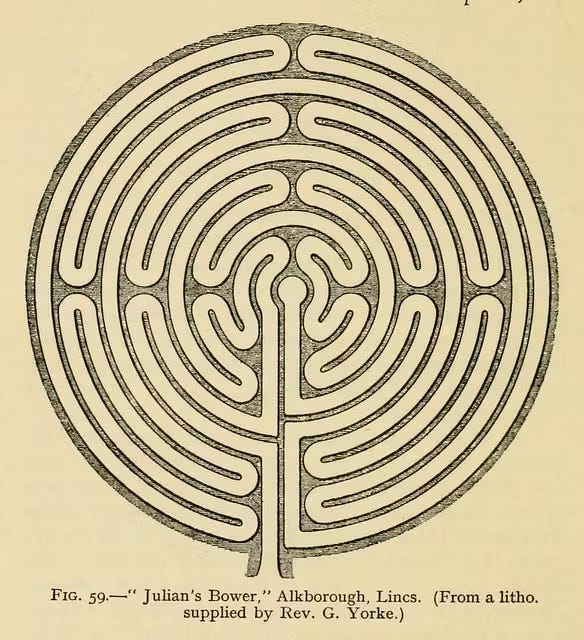

Now, think about this: Is your class more like dialogues or like the notoriously infamous lesson delivered by the economics teacher from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off?

I don’t know if you remember, but that economics teacher became famous because he would explain, explain, explain — in an evidently monotonous way — and then ask a question, wait two seconds, and answer the question himself. Maybe you’re the kind of teacher who does the same or maybe you don’t even bother asking questions. But that’s a problem, and I think I can prove it.

I learned this from the amazing educator/neuroscientist Jared Cooney Horvath. In one of the lessons from the course he created, The Learning Blueprint, he asks something like this:

You’ve seen a 50-cent coin thousands of times, right? So why can’t you draw one from memory? Now, think of any jingle or an annoying little tune from a commercial. Can you remember the lyrics?

You’re much more likely to remember the jingle than the details of the 50-cent coin. And the reason is simple: being exposed to something (or content) thousands or even millions of times doesn’t guarantee learning. What guarantees learning is applying it.

In other words: You don’t remember the jingle because you heard it many times. You remember it because you sang it many times.

This is called retrieval practice. The repeated practice of recalling information is essential for consolidating semantic memory (memory of concepts) and, therefore, for long-term learning. It’s not enough to just expose students to content; you need to let them apply it in some way. A lesson can’t be completely passive. It needs to be active. So, after presenting new content, set aside a few minutes to allow students to actively practice it.

Around the middle of the lesson, or right after introducing new content, you can ask an open-ended question like: What have we covered so far? Or something more specific: Write down two concepts I explained today and their definitions, or simply What does this mean?

But remember: each student must have time to try to retrieve the answer individually. So don’t be afraid of silence (we need it to think). After about a minute, you can then ask students to share in pairs or groups. Remember think-pair-share? That’s the idea.

Read more:

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological science, 17(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

Roediger, H. L. III, Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. In J. P. Mestre & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 1–36). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387691-1.00001-6

STRATEGY 3 – Concrete Examples

You walk into class to talk about exponential equations, the third conditional, the Krebs cycle, or the French Revolution. At some point, you realize your students are completely lost. Why is that?

In fact, why do you think I chose these four examples — one from math, one from English, one from biology, and one from history? And why do you think I mentioned mise en place, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, the teacher from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the 50-cent coin, and jingles?

(By the way, I just randomly remembered the “Pôneis Malditos” ad, a silly Brazilian commercial with animated poneys singing an annoying tune! See how our brain works?)

The equation is simple: when it comes to understanding abstract concepts, nothing beats the power of concrete examples. Our brain processes and memorizes complex information more easily when it’s presented in a tangible way. Creative teachers have long used everyday objects to illustrate complex ideas. For example, a geography teacher who brought in an avocado to explain the Earth’s layers and core. Or a chemistry teacher who used a sealed shoebox and a small crayon box to illustrate how scientists test things they cannot see or open — both of them were my teachers, by the way. These concrete examples not only make learning more vivid but also help students internalize difficult information more effectively by connecting these new concepts to stuff they already know.

In other words: instead of spending a ton of time creating amazing slides or all kinds of printed materials, bring a brick to class or any tangible object that connects with what your students already know. Use references from TV shows, movies, and books.

Read more:

Nebel C. (2020). Considerations for applying six strategies for effective learning to instruction. Medical Science Educator, 30, 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01088-8

Rawson K. A., Thomas R. C., Jacoby L. L. (2015). The power of examples: illustrative examples enhance conceptual learning of declarative concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 27(3), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9273-3

CONCLUSION

What does an effective lesson look like then? The lesson should start with everything organized for everyone, with questions about the topics to be covered, and more questions halfway through (after content exposure), with time for individual thinking (without looking at the material or notes), and with concrete examples and real objects (including pop culture references and analogies).

It seems obvious, right? And you know what? Most of us are already doing these things. This is how our brain learns more effectively according to the evidence we have from neuroscience, psychology, and education. If we understand the principles behind how humans learn and make a point of using strategies aligned with them more systematically, we can certainly help those we teach.

But here’s the funny thing. Even if your lesson doesn’t look anything like that, some students will learn. In fact, a principle from the Mind, Brain, and Education science is:

Learning is what the brain does

There are so many variables at play in the classroom (and outside of it) that we can absolutely say that learning can be quite chaotic. What if I just talked the whole lesson or told my students a story? What if they spent the whole lesson working on book activities and checking the answer key? What if they couldn’t bother to pay attention in class but somehow got hooked at home while watching a documentary or reading a book? Anything can happen, sure, but following well-researched principles of how our attention is connected to working memory and how what we are exposed to becomes long-term memory is wise, wouldn’t you agree?

My final message here is that teachers know best. We have the background to make the decisions that will impact our students’ outcomes. Some things are out of our hands too, no doubt. Don’t look at the science of learning as a tyrant imposing what you need to do in every lesson. Instead, look at it as a powerful ally that can help you make better decisions informed by evidence. Just as you’d do when seeking medical advice or figuring out how to invest your money or even deciding how to help your child going through a tough period. There are tons of experts who study these issues and put ethics above all.