How to become a memory champion and why that won't help you learn as much

Many people are fascinated with improving their memory so they can remember vast amounts of information. The paradox is that although it can be done, that probably won't be great for learning

One of my favorite shows on Netflix is the series Explained. It started with very short episodes explaining things that ranged from K-POP to sex, money, astrology, and dieting. The format appealed to my curiosity and hooked me instantly. Each episode had a celebrity narrator, great visuals, scientists and other experts, and testimonials from pertinent guests. What I’m saying here is: I highly recommend it!

But then came a spinoff that was right up my alley. The Mind, Explained kicked off its pilot with an episode on human memory. Imagine being able to memorize the exact order of a shuffled deck of 52 cards in under two minutes. These people exist. They’re called memory athletes, and there are competitions around the world. Yanjaa Wintersoul is featured in the first episode of this series, and she explains how she was at some point the holder of the world records in images, names & faces, and words memorized.

But I think you’re not fully grasping her feat. She was able to memorize 360 images in 5 minutes, 212 names and faces in 15 minutes, and 145 words in 5 minutes. Now you’re probably thinking that you can’t even remember your best friend’s phone number and you keep forgetting people’s names, right?

There’s more. Can you imagine remembering every single day of your life in vivid detail down to the date and even hour? What you wore, what you ate, who you talked to, what was in the newspaper… Sounds like a superpower, right? These people also exist. They have hyperthymesia, also known as Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM), a condition that makes forgetting nearly impossible. Watch Marilu Henner talking about that below:

Both memory athletes and hyperthymesic people make us wonder about how memory really works and what insights we could get to apply in everyday life demands, particularly studying. That’s what this post will discuss, but, first, a test.

What memory?

Do you have good memory? How many times have you heard this infamous question in your life? I bet you can’t remember :). Here’s something that might help you answer it:

TEST 1: Try to go back in time using your memory and remember what you had for lunch yesterday. Got it? What about two days ago? A little harder? And three days ago? What about four? Five? How about ten days ago?

TEST 2: Using your memory, try to write down your 5 of your closest friends’ phone numbers.

TEST 3: What year did the French Revolution start?

TEST 4: Close your eyes and visualize your house / apartment / classroom / office. Can you locate objects and even people in these spaces?

Well, I’ll take a chance and say you probably had a lot of difficulty remembering your lunch after you passed the 2-day threshold, am I right? I am quite confident you couldn’t even remember 1 phone number. If you like History, you may have been able to answer TEST 3, but I bet TEST 4 was a lot easier, right?

EXTRA TEST: Imagine you’re teaching that group of 10, 15, or 20 students that you’ve had for a while. Close your eyes and try to remember where everyone is seated.

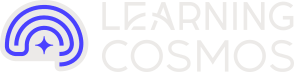

I know what you’re thinking: “My lunch is different every day (or most days) and my students always sit in the same place.” You’re right! That’s one of the reasons why you can remember their positions more easily. Another reason is the fact that humans have quite good spatial memory and not that great declarative memory (explicit memory), which is the conscious part of our memory in charge of storing concepts, experiences, and facts (Ullman, 2004).

The fact is: there are many types of memory systems. According to Gazzaniga (2009), here’s how complex human memory is.

But one thing is certain. We can navigate the space around us quite effectively and this probably developed to help early humans better protect themselves against predators, retrieve the location of safe havens, and find animals to hunt and food in the territory (Foer, 2011). Be it as it may, our spatial capabilities could be put to better use when it comes to memorizing other types of information.

Hippocampus: the master of memory

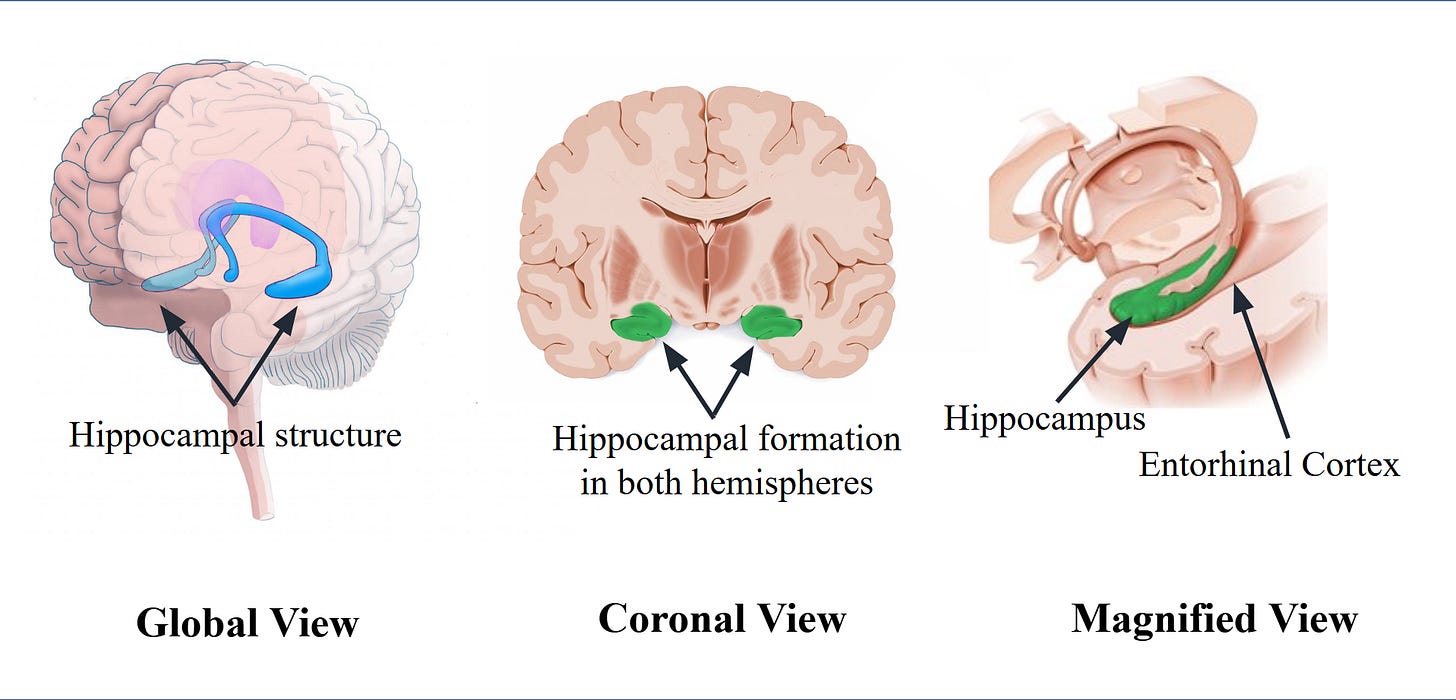

Located in the medial temporal lobe, the hippocampus is responsible for memory formation and storage (Bird & Burgess, 2008) as well as spatial navigation (Maguire et al. 2006). As I wrote in a previous blog:

The most studied brain in neuroscience history has also made its contribution to the idea of a 15-min rule. Henry Molaison, known as HM for decades because of doctor-patient-science confidentiality, had parts of his hippocampi removed in surgery to stop seizures. After the procedure, although his seizures were cured, Henry suffered from short-term memory loss being unable to form long-term explicit memories. He could remember a random 3-digit number or names of people he had just met for no more than 15 minutes (Squire, 2009)

Surrounding the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex acts as a communication hub with the neocortex, the largest area of the brain, which is divided into four lobes and manages our higher mental functions, perceptions, and behavior (Hafting et al. 2005; Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2014).

Inside the entorhinal cortex, we find grid cells, specialized neurons that play a vital role in our ability to understand space and even perceive time (Hafting et al. 2005). It's like having a built-in GPS, and it turns out that GPS is incredibly helpful when it comes to learning and memory.

In fact, studies led by the late Professor Eleanor Maguire at University College London revealed that London taxi drivers have a significantly larger posterior hippocampus than the average person. These drivers are renowned for mastering an incredibly demanding test called “The Knowledge”. It requires them to memorize over 26,000 streets and thousands of landmarks (without using Google Maps or Waze, I must add)

The memory palace technique

As the legend goes, Simonides of Ceos, a Greek poet hired to entertain the guests of a banquet, was spared from a horrible death moments after he left the palace, which collapsed, leaving the guests unrecognizable. But Simonides, having glanced at the guests’ seating arrangement, helped identify each body by mentally walking through the room and pointing out who sat where (Yates, 1966).

And that’s the origin of the Memory Palace Technique, which is widely used by memory athletes. It is said that politicians, artists, and even emperors and kings used this technique to memorize messages, lyrics, and speeches. The idea is quite simple, actually. All we have to do is imagine a building, a house, or an apartment, for instance. It helps if it’s our own house since we’re very familiar with the different rooms. Now, in every room of this house, place the information you want to retrieve. Another trick is to create bizarre images that you can easily go back to when needed.

Let’s say students in an English class are learning Modals for Speculating. They could imagine they’re entering their house and, right on the floor of their living room, there’s a crime scene and a giraffe or a gorilla detective. A robbery or a murder, perhaps. They can see some evidence, and they need to think of a possible explanation before the detective’s interrogation: “The criminal must have entered through the window… might have picked the lock… can’t have copied my key.”

Now, imagine these students need to retrieve Professions (vocabulary). They could visualize in their kitchen a lawyer-zombie being operated on by a vampire surgeon, while stick-figure journalists snap photos and a cat in a chef’s hat prepares a delicious meal.

I know this may sound silly. But that’s the point!

A well-established concept that explains why the memory palace can be so helpful is the Elaborative Encoding Theory (Karpicke & Smith, 2012). It suggests that information should be encoded in various ways (visually, verbally, spatially, emotionally) for it to be more easily retrieved. This complements Paivio’s Dual Coding Theory, which proposes that verbal and non-verbal processing work together to solidify memory (Paivio, 1986).

If you're still skeptical, let’s talk about Joshua Foer—a journalist with a so-so memory who trained using these very techniques. In 2006, he won the USA Memory Championship, memorizing all sorts of random information using nothing more than memory palaces and strange mental imagery. His journey is documented in his best-selling book Moonwalking with Einstein (Foer, 2011).

Why that might not help you learn

I’m always impressed with memory athletes. I think we can all agree that they can perform astonishing feats of recall. But I’d like to argue here that their techniques may work as much as we’d like for students aiming for long-term learning and retention. As memory champions Ron White and Tom Goves discussed on Quora, most of the memorized content fades within hours or days unless it's systematically reviewed.

Ron White emphasizes that:

Any mental athlete could remember any number sequence or deck of cards sequence for as long as they wanted as long as they reviewed it enough. Typically review it:

- a few hours later

- 1 day later

- 2 days later

-3 days later

- 1 week later

- 2 weeks later

- 3 or 4 week laterIt should go in to long term memory then

Based on this discussion, here are some insights for you:

Memorizing lots of information fast does not guarantee long-term learning

We can (and should) rely more on our spatial navigation skills to help us learn

Changing contexts, moving around

Attention - and effort - is required when we encode new memories

Retrieving is an effective way to strengthen memories

Forgetting and spacing are absolutely essential for long-term consolidation

Here’s something I pulled from a previous post:

What should we be doing more then? The answer comes the concept of spacing. As Kornell and Bjork address right at the beginning of their 2008 paper:

The spacing effect refers to the nearly ubiquitous finding that items studied once and revisited after a delay are recalled better in the long term than are items studied repeatedly with no intervening delay (e.g., Cepeda, Pashler, Vul, Wixted, & Rohrer, 2006; Dempster, 1996; Glenberg, 1979; Hintzman, 1974; Melton, 1970). The positive effects of spacing on long-term recall are large and robust, and have been demonstrated in a variety of domains, such as conditioning (even in animals as simple as Aplysia; see Carew, Pinsker, & Kandel, 1972), verbal learning (e.g., Bahrick, Bahrick, Bahrick, & Bahrick, 1993; Ebbinghaus, 1885/1964), motor learning (e.g., Shea & Morgan, 1979), and learning of educational materials (e.g., Bjork, 1979; Dempster, 1988)

Looking for Better Retention? Combining the book with Spaced Repetition

Is using a coursebook really the best way to teach or learn? There’s a growing debate in education about whether our heavy reliance on textbooks is helping or hindering student learning. Much of this debate focuses on how the syllabus is put together, if content sequence is based on how we actually learn or if books offer more - or fewer - opportunities…

As memory champion Tom Graves puts it:

[…] the main stuff will fade away after an hour or two, and you actually want that to happen. When I first started practising I used to memorise a single pack of cards a day, because after 24 hours while I'd still be able to remember yesterday's pack (mostly), it would have faded enough that I'd be able to tell the difference between that one and the one I'd just memorised which would be fresher. If I did more than one the same day it would get confusing.

As mentioned before, attention and effort are key ingredients in memory formation. Watch the Netflix series or google any memory competition to see how focused everyone is while trying to memorize hundreds of digits. Take the case of London taxi drivers again. They actively paid attention, studied routes, mentally rehearsed paths, and were constantly tested by real-world navigation challenges. In contrast, we can think about using apps like Waze or Google Maps. They remove the burden of memorization and that means we’re passively being guided by them. Do you think you can drive back to a place you’ve to before without using the GPS? Think again.

What does that tell us about using generative AI in education? I suppose the message here is. I can safely say that the same principles apply to learning. Relying too much on external aids and shortcuts reduces the deep processing that helps us remember. It's the struggle to retrieve and organize information that strengthens our memory over time, not so much how much information we can quickly absorb. However, if you still want to become a memory champion, here’s some help:

Joshua Foer – Feats of Memory Anyone Can Do TED

How to Create a Memory Palace – WikiHow

https://www.wikihow.com/Build-a-Memory-Palace

References

Bird, CM, & Burgess, N. (2008). The hippocampus and memory: Insights from spatial processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(3), 182-18294.

Dossani, Missios, & Nanda. (2015). The Legacy of Henry Molaison (1926–2008) and the Impact of His Bilateral Mesial Temporal Lobe Surgery on the Study of Human Memory. World Neurosurgery, 84(4), 1127-1135.

Eichenbaum, & Cohen. (2014). Can We Reconcile the Declarative Memory and Spatial Navigation Views on Hippocampal Function? Neuron, 83(4), 764-770.

Foer, J. (2011). Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything. New York: Penguin Press

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2009). The cognitive neurosciences. MIT press.

Hafting, T., Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Moser, M. B. & Moser, E. I. Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature 436, 801–806 (2005).

Karpicke, J. D. & Smith, M. A. (2012). Separate mnemonic effects of retrieval practice and elaborative encoding. Journal of Memory and Language. 67 (1): 17–29

Maguire, E., Nannery, R., & Spiers, H. (2006). Navigation around London by a taxi driver with bilateral hippocampal lesions. Brain, 129(11), 2894-2907.

Nadel, L,. O'Keefe, J. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Nielsen, T. (2013). The method of loci (MoL) and memory consolidation: Dreaming is not MoL-like. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences,36(6), 624-5.

O'Keefe, J., Nadel, L. (December 7, 1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental Representations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ullman, MT (2004). "Contributions of memory circuits to language: the declarative/procedural model". Cognition. 92: 231–70.

Yates, F. (1966). The Art of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago