Neuromyths Part 1: Origins and Dangers

A lot of people believe in claims about the brain and learning that simply make no sense. Where are they getting those from? This is the first in a series of posts about the popular neuromyths

We only use 10% of our brain

Ever heard anyone say that? One of the last times I did was from one of the most powerful voices in recent movie history: Morgan Freeman’s. If he had been born in the UK, I’m sure he would’ve been knighted by now and joined the select group that includes Sir Anthony Hopkins, Sir Ian McKellen, Dame Judi Dench, and Dame Helen Mirren. Mr. Freeman played the role of Professor Samuel Norman, a brain expert who has studied, among other things, the evolution of this incredible organ in Lucy, a movie co-starring Scarlet Johansson.

In one of the scenes, Professor Norman is lecturing to a group of interested students and says:

“Imagine for a moment what our life would be like if we could access, let’s say, 20% of our brain capacity?”

He goes on and claims that each human being has 100 billion neurons, from which only 15% are activated and that means that “we possess a gigantic network of information to which we have almost no access”. In his words, if we could access all the potential of our brains, we’d be able to control other people and even matter.

Well, Morgan Freeman, even though I love your voice and your acting, your character couldn’t be further from the truth. In this Luc Besson movie, released in 2014, most of what Professor Samuel Norman says is a false claim about the brain. It’s a neuromyth.

Funnily enough, I met the real Professor Samuel Norman - sort of. His name is Paul Howard-Jones and he is one of the biggest brain references in the world and a professor at the School of Education at the University of Bristol. I’m quite privileged to have been one of his students. In his book, Evolution of the Learning Brain: Or How You Got To Be So Smart, Howard-Jones (2018) goes back in time to the early forms of life and takes us on a journey throughout the eons of our home planet until the most sophisticated form of intelligence known to date: our brains and us. He has published many articles and books on the potential of using brain research, and neuroscience-informed strategies to positively impact educational achievement and learning outcomes.

Paul Howard-Jones signing my copy of his book during the launch in 2018

Well, Prof. Samuel Norman played by Mr. Freeman, let’s stick to the facts.

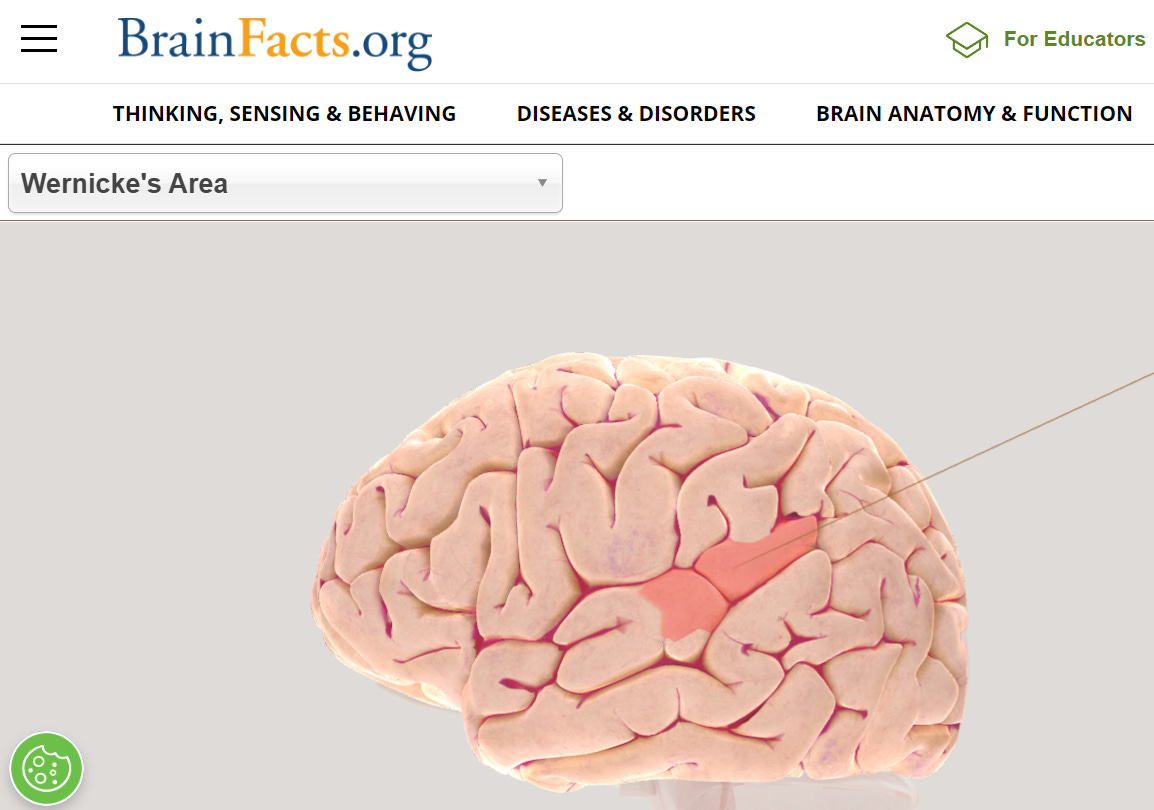

No, we do not use just 10 or 15% of our brain capacities. In fact, we use most of our brain most of the time, even when we are sleeping. A simple task such as drinking coffee will require many areas of your brain to activate synchronously. The frontal lobe when you decide to look at the cup of coffee and pick it up, the occipital lobe because you’re visually processing the stimulus, subcortical areas such as the ventral tegmental area, and the nucleus accumbens, integral parts of your reward system, because the thought of fresh coffee and that expectation will make you release dopamine. Your parietal lobe’s somatosensory cortex will also be active as you grab the cup and feel the heat on your fingertips, as well as areas related to taste and smell, memory retrieval, etc. You can learn more about brain structure and function on:

https://www.brainfacts.org/

Where did it come from?

The exact origin of the myth is not very clear, but it probably came from a misinterpretation of early brain research or from, and this makes a lot of sense to me, motivational speakers who exaggerated the idea of human potential. A Scientific American article by Barry L. Beyerstein of the Brain Behavior Laboratory at Simon Fraser University might shed some light on this mystery:

My attempts to track down the origins of the 10-percent myth have not discovered any smoking guns, but some tantalizing clues have emerged (more are recounted in the references below). One stream leads back to the pioneering American psychologist, William James, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries […] James always talked in terms of one's undeveloped potential, apparently never relating this to a specific amount of gray matter engaged. A generation of "positive thinking" gurus that followed were not so careful, however, and gradually "10 percent of our capacity" morphed into "10 percent of our brain."

Barry Beyerstein also mentions in the article that this myth may have been spread by Lowell Thomas’ preface to Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People, one of the most popular self-help books in history. He even mentions the possibility it came from something Albert Einstein may have said. Wherever it came from, the idea that we only use 10% of our brain is a neuromyth. Let me explain what that is.

Let’s start with the 2002 OECD report, "Understanding The Brain: Towards a New Learning Science". It basically summarized discussions on learning across different age groups and debunked common misconceptions about the brain, like the "left-brain vs. right-brain" dominance or the 10% brain usage myth. This was the report that introduced the term "neuromyth" for such false beliefs. More importantly, it highlighted key findings: the brain's ability to learn and change (neuroplasticity), the impact of emotions and environment on learning, and a deeper understanding of language and numeracy acquisition.

New tech and neuroimaging studies

If you ask any neuroscientist today, at least the serious ones who don’t believe in conspiracy theories, they’ll tell you the idea of using only 10% of the brain is ludicrous. The brain is a resource-intensive organ and damage to any part has consequences. What’s more, brain scans don’t support that notion. Researchers and physicians use methods such as magnetoencephalography, PET scans, electroencephalography, and functional MRI machines to create amazing images of the human brain.

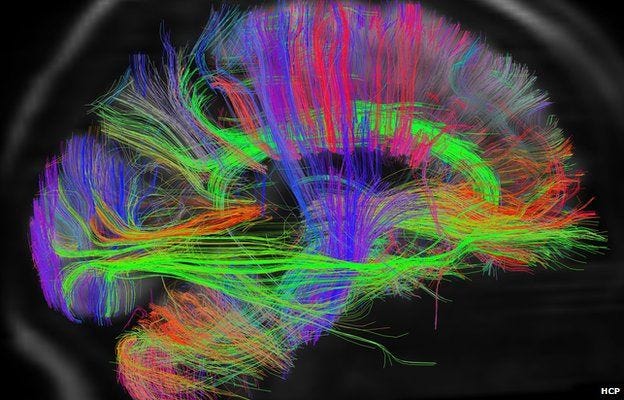

My favorite image is the one below. It was achieved through diffusion tractography and it shows the reconstruction of neural connections.

There are other creative techniques to understand the brain and what it’s made of. In fact, it’s time we shared something with Morgan Freeman’s character again. No, Samuel Norman, we don’t have 100 billion neurons in our brains. Actually, according to the amazing Brazilian neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel, we have around 86 billion. You can watch her brilliant TED Talk about how her method helped get to that number. In short, it involved dissolving the brain cells (excluding the nuclei) with a detergent, resulting in a "brain soup”, and then counting the remaining nuclei, which represent individual neurons, and extrapolating the number according to our brain’s volume. Fascinating, isn’t it?

The general population and neuromyths

Suzana Herculano-Houzel (2002) was also responsible for a questionnaire that has been replicated all over the world on how much the general public, and most recently, teachers, know about the brain.

The results in Brazil suggested that most people don’t really know much about how the brain works. So did the results in the UK, as demonstrated in Howard-Jones’ article (Dekker et al. 2012), in Portugal (Rato et al. 2013), in Greece (Papadatou-Pastou et al., 2017) in Latin America (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2015), in China (Pei et al., 2015), in Spain (Ferrero et al., 2016), and virtually everywhere.

I know what you’re thinking.

But André, wasn’t it you who published an article some time ago claiming that knowledge of neuromyths might not help people become better professionals, especially teachers?

You’re not wrong. I wrote that. You can read it below if you like.

Learning about Brain Science and Neuromyths will probably not make you a Better Teacher

How ironic. If you know me, you're aware that I've dedicated at least 7 years or so of my life to fighting against mis(dis)information in teaching and learning. In 2017 I joined the BRAZ-TESOL Mind, Brain, and Education (MBE) SIG and in the following year, I started my master's prog…

Here’s a spoiler, though. Just because we don’t understand how the brain works, it doesn’t mean we can’t be great teachers. In fact, we might even believe in many neuromyths and pseudoscience and still be better teachers than those who are more scientifically literate. Does that mean we shouldn’t care about debunking neuromyths? What’s the point of this blog post?

The point of this blog post series

In Lucy, Scarlet Johansson unlocks her brain potential because of a synthetic drug and basically gains superpowers that would make her fellow Avengers in a different franchise incredibly jealous. Let’s just say that if Natasha Romanoff were Lucy in the latest Avengers movies, Thanos wouldn’t have gone so far at all. That brings me to my main question(s) for you to reflect on. What impact do characters like Prof. Samuel Norman (both in fiction and real life) have on people’s understanding about the brain? How do books, academic, self-help, or literary shape what people know about how nature and biology works?

Maybe not knowing how the brain learns won’t translate to not being able to plan and deliver an effective lesson. But think of all the money lost to publishing materials with false information that will need correcting someday, or to buying courses from people who share neuromyths (knowingly or not). What about basing our lives on bogus claims made by self-appointed gurus in books? Or the false hope of finding a way to unlock the “other” 90% of our brain power with some ancient technique or modern drug? Isn’t it a good idea for all of us to learn more about how our brains work to at least avoid scams?

I mean, just think what could happen if more educators around the world actually understood some fundamental principles of brain structure and function and used that knowledge to reflect on their practice and help their students. That’s the point of this blog series. I want to share some of the most popular misconceptions about the brain and how we learn and what the research tells us about these things.

While we are at it, let me just point out that many myths certainly deserve our attention and you’ve probably heard of them. The matching hypothesis of the learning styles theory and the left/right-brained paradigm are just a few I want to explore in the coming blog posts. (Dekker et al. 2012)

I’m planning a 5-blog post series. The idea is to raise awareness and promote a discussion. It is, however, essential to remember that what I’m proposing is not a recipe for successful teaching, though. Like I said, just because you might learn one or two things about the brain and learning, it might not make you a better teacher, There are so many variables to consider that we can’t say “Do this, or follow these 5 steps or strategies and everyone will learn more effectively”. Neuroscience has advanced a lot in the last couple of years, but there’s so much we don’t know yet and what we do know can’t always be translated into teaching practice.

The journey is long for those who are interested in following the path. A good place to start this journey into the depths of our brain, besides Paul’s book, is Jared Cooney Horvath’s YouTube channel.

Paul Howard-Jones’ webinar for the BRAZ-TESOL Mind, Brain, and Education Special Interest Group. Mirela Ramacciotti, Rodolfo Mattiello and I helped organize the event

As a geek, I’ll continue to watch sci-fi movies. One of my favorite series now is the 3 Body Problem on Netflix. Although I know many of the things depicted in the series are complete nonsense, I love it. I will, however, embrace the inner nerd here and be skeptical about everything we see in movies, read in books, and hear from people promoting new services and products… and I hope you do too. Stay tuned for the next blog post in the series.

REFERENCES

Dekker, S., Lee, N., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 429-429. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

Ferrero, M., Garaizar, P., & Vadillo, M. A. (2016). Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence among Spanish Teachers and an Exploration of Cross-Cultural Variation. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 10, 496. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00496

Gleichgerrcht, E., Lira Luttges, B., Salvarezza, F., & Campos, A. (2015). Educational neuromyths among teachers in Latin America. Mind, Brain, and Education, 9(3), 170-178.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2002). Do you know your brain/ A survey on public neuroscience literacy at the closing of the decade of the brain. The Neuroscientist, 8(2):98-110

Howard-Jones, P. (2018). Evolution of the Learning Brain: Or how you got to be so smart. Taylor & Francis Group

Papadatou-Pastou, M., Haliou, E., & Vlachos, F. (2017). Brain Knowledge and the Prevalence of Neuromyths among Prospective Teachers in Greece. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 804. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00804

Pei X., Howard-Jones P. A., Zhang S., Liu X., Jin Y. (2015). Teachers’ Understanding about the Brain in East China. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 174, 3681–3688. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1091

Rato, J., Abreu, A., & Castro-Caldas, A. (2013). Neuromyths in education: What is fact and what is fiction for Portuguese teachers? Educational Research, 55(4), 441-453.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2014). Making classrooms better: 50 practical applications of mind, brain, and education science. First Edition. New York: W.W Norton & Company.

This is just amazing!!! 🤩 Dispelling neuro myths like the idea that we only use 10 or 20% of our brains is so important! These misconceptions about human potential and capabilities can lead to harmful practices or wasted efforts in trying to unlock ‘unused brain power’ We have similar initiatives in our Envelheciencia project, which is actively engaging with teachers from primary schools to raise awareness about aging, dementia, and also debunking such myths. Keep up the great work!