Outsourcing Thinking: Will AI Atrophy Our Brains?

With generative AI, we must ask: are we building better thinkers or just better users of technology? What is cognitive offloading, why does it matter, and what happens when all systems fail?

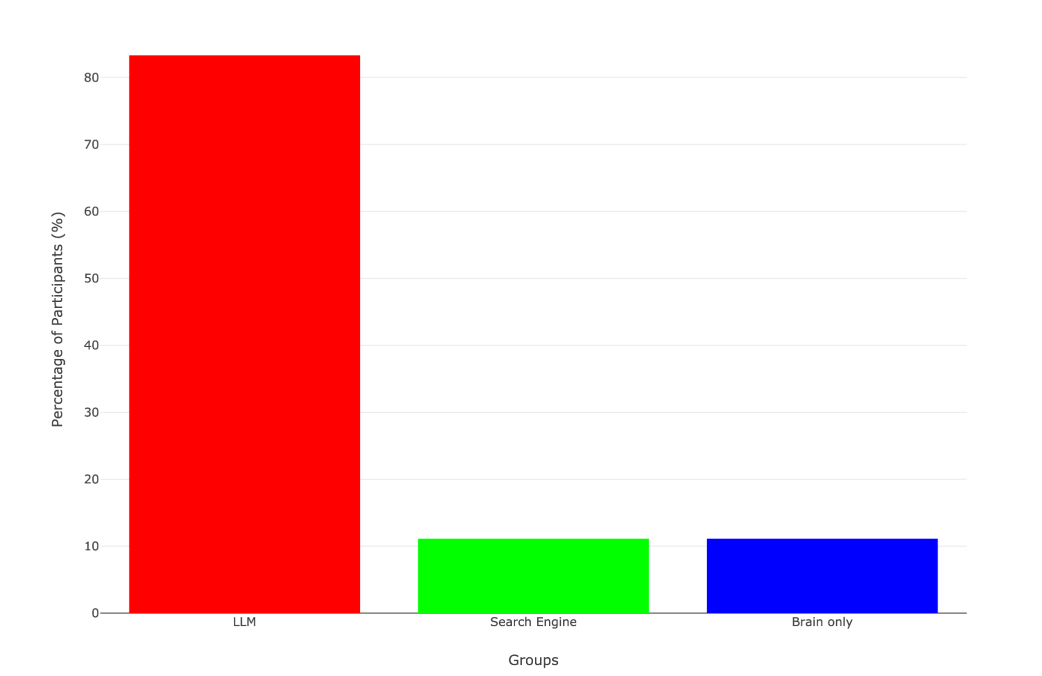

I have spent the better part of the last year talking about the advantages and disadvantages of using generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education. Most of what I discussed was based on my own knowledge of how the brain learns and on learning experts’ opinions. After all, not much had been published on the topic. However, a few days ago, I came across a study by MIT that made me pause. It basically stated that students who used AI to write an essay showed noticeably weaker neural connectivity across the board. Quite literally, their brains were doing less work when AI was in play, which is not really a shock when you think about it. But what truly alarmed me was that over 80% of the ChatGPT users couldn’t recall even a single correct quote from essays they had written just minutes before:

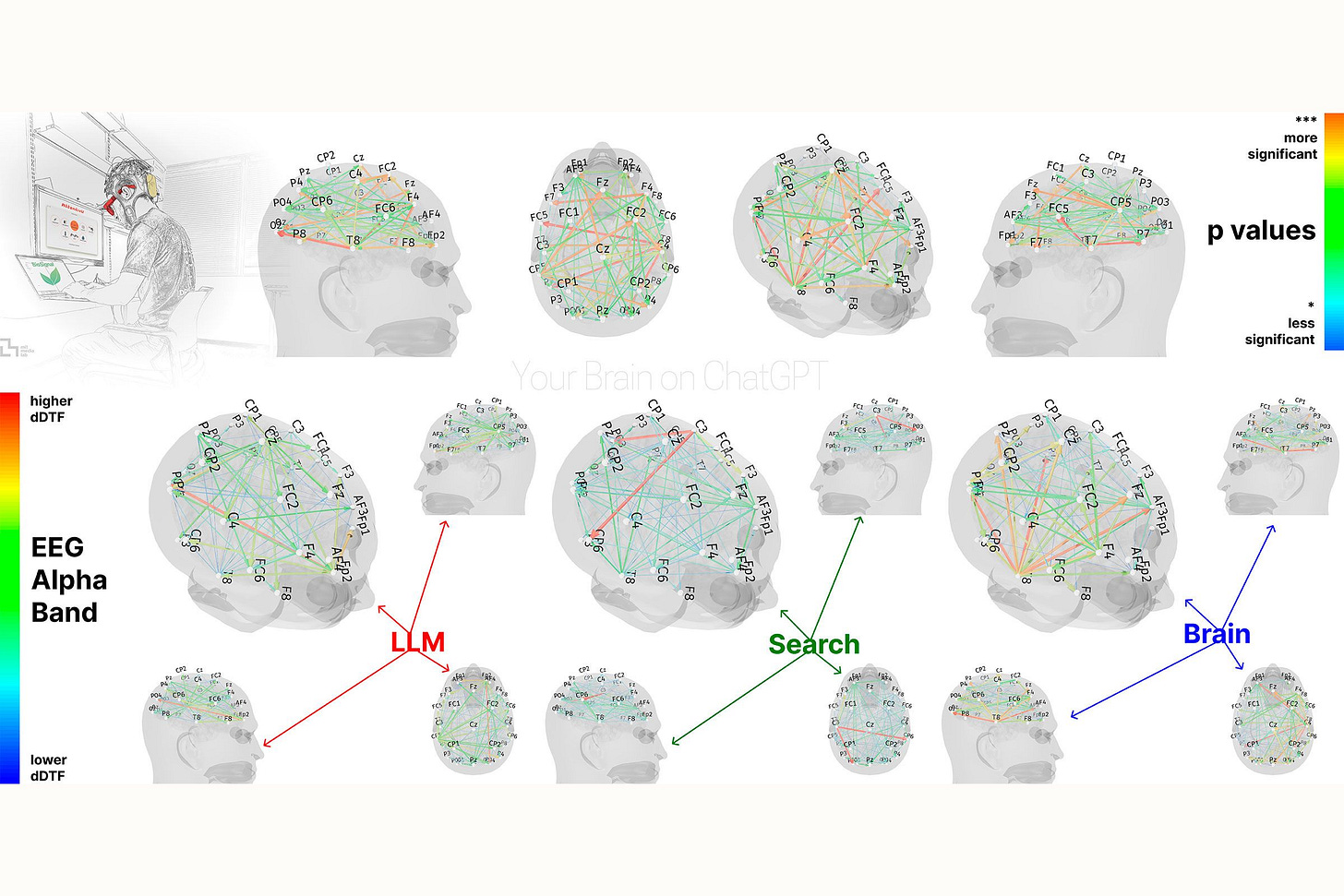

EEG analysis presented robust evidence that distinct modes of essay composition produced clearly different neural patterns reflecting divergent cognitive strategies…Brain connectivity systematically scaled down with the amount of external support: the Brain-only group exhibited the strongest, widest-ranging networks, Search Engine group showed intermediate engagement, and the AI assistance elicited the weakest overall coupling

Are we doomed? Will AI atrophy our brains? Are we going to become zombies who can’t think critically?

Well, to answer that, first you need to know a couple of things about this study and how it’s been advertised. Time Magazine wrote:

ChatGPT May Be Eroding Critical Thinking Skills, According to a New MIT Study

The New York Post:

ChatGPT is getting smarter, but excessive use could destroy our brains, study warns

And the Daily Mail:

Using ChatGPT? It might make you STUPID: Brain scans reveal how using AI erodes critical thinking skills

It’s kinda funny. There’s a certain poetic irony in what’s been happening with the latest AI and education debate. This MIT study went viral for supposedly proving that ChatGPT is making students’ brains shut down. Many headlines basically screamed “AI is destroying your brain!” or “ChatGPT is killing critical thinking skills”. Social media exploded. People started posting and writing about it (aren’t I a hypocrite?), and how did most people react? Well, they used AI to summarize the paper, without actually reading it.

So here’s what you need to know. Researchers tracked the brain activity of 54 university students, 18 to 39-year-olds from the Boston area, for four months using EEG scans while they wrote SAT-style essays, with and without AI assistance. In case you’re wondering, EEG stands for electroencephalography, and it’s a non-invasive method used to measure electrical activity in the brain. Small electrodes are placed on the scalp to detect and record brain wave patterns.

These students were split into three groups to write a series of essays:

The LLM group used ChatGPT

The Search group used Google

The Brain-only group didn’t use anything but their brains

As can be seen in the image below, neural activity is significantly lower in the LLM group. In other words, students who used ChatGPT sort of “turned off” their brains and relied on the world-famous Ctrl + C - Ctrl + V strategy.

What most articles fail to mention is that researchers combined the EEG results with a Natural Language Processing (NLP) analysis. The Brain-only group showed the most diverse writing styles and topic approaches, while the LLM (ChatGPT) group produced highly uniform, statistically homogeneous essays with little variation. The Search Engine group fell somewhere in between, shaped by their own search questions and search engine optimization biases. Interestingly, while the Brain-only group reflected more personal and socially-influenced perspectives (like referencing Instagram), they used significantly fewer named entities (NERs) such as specific people, places, and dates (60% less than the LLM group). The LLM group used the highest number of NERs, with the Search group using about half as many.

Even more interestingly, two human English teachers evaluated the essays (blindly) and described the AI-generated essays as “soulless”. They mentioned that the essays were technically polished, grammatically and structurally sound, but emotionally flat and without personal insight. In other words, these essays often sounded academic and covered topics in depth, but lacked individuality and an authentic voice.

As predicted, students who relied on ChatGPT wrote faster, but didn’t engage their brains as much because they literally didn’t have to make such a mental effort. The most striking result was that minutes after finishing an essay, they couldn’t recall what they had written.

There’s a major catch, though. A few, actually. The sample size of the study was really small. It started with 54 participants, but by the end of the study, only 18 participants remained, and they were divided into two groups of 9. So the conclusion was based on only 9 participants who had to write without ChatGPT. Also, they were all from the same area and were young. They were not tested before to establish a baseline of their critical thinking/writing skills, and who says an SAT-style essay is a reliable measurement of thinking critically?

Oh, and the paper was not peer-reviewed…

OK, so what does it all really mean?

Let the paper do the talking here:

Taken together, the behavioral data revealed that higher levels of neural connectivity and internal content generation in the Brain-only group correlated with stronger memory, greater semantic accuracy, and firmer ownership of written work. Brain-only group, though under greater cognitive load, demonstrated deeper learning outcomes and stronger identity with their output. The Search Engine group displayed moderate internalization, likely balancing effort with outcome.

The LLM group, while benefiting from tool efficiency, showed weaker memory traces, reduced self-monitoring, and fragmented authorship. This trade-off highlights an important educational concern: AI tools, while valuable for supporting performance, may unintentionally hinder deep cognitive processing, retention, and authentic engagement with written material. If users rely heavily on AI tools, they may achieve superficial fluency but fail to internalize the knowledge or feel a sense of ownership over it.

Despite the shortcomings of this MIT paper, the conclusion is that when people rely on AI to get something done for them, they don’t seem to learn much. This aligns with the concept of cognitive offloading, a term that describes what happens when we let external tools (like AI) do our thinking for us. This is a lot more present in our lives than you might think. If you have ever…

Used a calculator to add your bills

Made a list before going to the supermarket

Used a bullet journal or a digital calendar to set an appointment

Asked Alexa to remind you of someone’s birthday

… that means you’re familiar with cognitive offloading. We might argue that the problem isn’t the offloading itself. It has more to do with the type and its overuse. Think of your brain like a muscle (even though it’s an organ). If you stop using it, it could atrophy. And unlike the biceps, you can’t just hit the gym for a month and get your cognitive flexibility back. It’s not that easy (not that hitting the gym was ever easy!)

As Carl Hendrick brilliantly put it:

When you first learn that seven times eight equals fifty-six, your declarative system dutifully records this information. […] With sufficient practice, seven times eight becomes not a fact to be retrieved but a response as automatic as breathing. […] When we constantly outsource basic operations to external systems, we prevent this crucial transition. Students may get correct answers, but they never develop the procedural fluency that enables genuine mathematical thinking

Hendrick was discussing another paper that came out recently. The Memory Paradox: Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI was written by Barbara Oakley, Michael Johnston, Ken-Zen Chen, Eulho Jung, and Terrence Sejnowski, and it says:

What happens if we shortcut the shift from declarative to procedural memory-making by instead using an external device? Simply put, if a learner leans too heavily on external aids, the “proceduralization” of knowledge may never fully occur. A student who always uses a calculator for basic arithmetic, for instance, might pass tests, but she may not develop the same number sense and intuition as one who has internalized those operations. The latter student, having memorized math facts and practiced operations, can recognize patterns (e.g. spotting that 12 x 100 = 1200) and estimate or manipulate numbers with confidence. The former student might solve every problem by brute force lookup or computation, never quite forming an intuitive grasp—the kind of intuition that often leads to creative problem-solving or spotting errors at a glance

The authors of this paper argue that memorized knowledge, or prior knowledge, is the scaffolding that allows us to reason, to solve problems, to detect errors, and yes, even to use AI wisely.

I think an analogy comes in handy. One of my all-time favorite movies is Mona Lisa Smile starring Julia Roberts. She plays Katherine Ann Watson, a history of art professor at the famous Wellesley College. There’s a scene that depicts a very interesting idea. Katherine Watson is inside a room with a very large table surrounded by her students. As she explains the legacy of one of the most brilliant painters of all time, Van Gogh, she picks up a box and hands it to one of her students:

With the ability to reproduce art, it is available to the masses. No one needs to own a Van Gogh original. They can paint their own. Van Gogh in a box, ladies. The newest form of mass distributed art: paint-by-numbers.

Her student reads from the box:

Now everyone can be Van Gogh. It's so easy. Just follow the simple instructions, and in minutes, you're on your way to being an artist

You can find these boxes in online ads with catchy phrases like: “With these DIY paint by numbers kits, anyone can feel like an artist”. Having been inside the Van Gogh Museum myself and looked in awe at this man’s breathtaking work, I must say I feel offended by slogans like that. Van Gogh worked really hard to achieve what he achieved, and no one can become him by simply painting over a canvas with numbers. Just imagine how much knowledge and how many skills our favorite Dutch painter accumulated over the years through practice and reflection.

I believe similar analogies apply here. Think about learning an additional language. If you want to learn Spanish and every opportunity you have to practice using your brain is replaced by using a device that translates what you say and hear, I think it’s quite obvious that you won’t learn, isn’t it?

There is a concern, however…

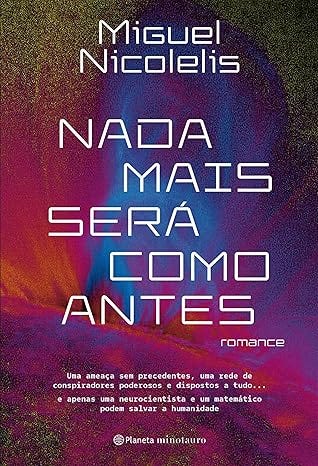

I’ve recently watched an interview with one of the most famous Brazilian neuroscientists. Miguel Nicolelis said something like (and I’m afraid I’ll be paraphrasing him here):

We’ve created an entire electro-electronic-digital society, and we’ve forgotten that we’re part of the solar system. There’s a star right next to us, and every now and then it gets in a bad mood and spits things out. What if all of this disappears in a solar storm? What happens then?

We’re indeed more and more dependent on electronic and digital stuff. Let’s say Nicolelis’ dystopian future actually happens. In fact, he’s written a novel about it. It’s called Nada Mais Será Como Antes (Nothing will be the same), and in this book, the author takes us on a journey to a future that might not be too far off. Drawing on his expertise, he depicts a scary but compelling picture of a world undergoing constant digitalization, pushing humanity away from its analog roots. As this transformation unfolds, we begin to see how people are becoming more and more disconnected from their own nature and increasingly manipulated by the agendas of the Overlords.

The interesting thing is that the universe described in Nicolelis’ book is an extrapolation of what’s already happening to a certain extent. Many people are easily manipulated by fake news fueled by their addiction to social media and lack of discernment. Some studies, although still controversial, have been showing a sharp decline in people’s average IQ (just look for reverse Flynn Effect and you’ll see).

Combine all of that with AI-generated image and video capabilities. It’s not far-fetched to assume that in a couple of years, humans will not be able to distinguish what is real from what is AI-generated. If what has been collectively built throughout generations of philosophizing, observation, and research can be easily erased or warped, what happens to humanity’s recorded prior knowledge?

Well, let’s take it a step down and reflect on the now. The truth is, AI isn’t going anywhere. The potential for creativity, productivity, accessibility, and progress is immense. But it’s a tool. Its impact depends entirely on how we use it. Give a hammer to a skilled carpenter and you get a beautiful piece of furniture. However, if in the future all furniture is produced by robots and 3D printers, who will be the skilled carpenters, and what will happen if the systems fail?

Eslen Delanogare, a Brazilian psychologist and neuroscientist who advocates for scientific literacy online, posted something on Instagram that serves as an important cautionary tale:

AI will be to the brain what transportation technologies were to the body. Just as we became physically sedentary and now need to set aside time to exercise our bodies, we will also become mentally sedentary and will have to train our brains.

You either understand this now and take action, or you’ll watch your reasoning abilities wither away in the coming years.

It’s about sequencing and balance. Students should build their cognitive foundations first. Struggle a little. Engage deeply. Then, and only then, bring AI into the process as a collaborator, not a replacement. The MIT paper itself suggested that:

while AI tools can enhance productivity, they may also promote a form of "metacognitive laziness," where students offload cognitive and metacognitive responsibilities to the AI, potentially hindering their ability to self-regulate and engage deeply with the learning material

A commentary published in Nature Reviews Psychology, led by Lixiang Yan and colleagues, suggests that although generative AI can boost learners’ performance, immediate performance is not learning. Just because AI can help students produce cleaner and more coherent text, it doesn’t mean those students are learning anything meaningful or lasting. As cited in Barbara Oakley’s paper:

Effective learning requires a balance: using external tools to support - not replace - the deep internal knowledge essential for genuine understanding. (Fernando et al., 2024)

I failed to mention something you should know. There were three essay writing sessions plus a fourth and final one. This one was different. Those who had been assigned to the Brain-only group now had to write using ChatGPT. And those who were in the LLM group (who had used ChatGPT before) now had to rely only on their brains. Guess what happened?

In session 4, LLM-to-Brain participants showed weaker neural connectivity and under-engagement of alpha and beta networks; and the Brain-to-LLM participants demonstrated higher memory recall, and re‑engagement of widespread occipito-parietal and prefrontal nodes, likely supporting the visual processing, similar to the one frequently perceived in the Search Engine group.

The LLM-to-Brain group's early dependence on LLM tools appeared to have impaired long-term semantic retention and contextual memory, limiting their ability to reconstruct content without assistance. In contrast, Brain-to-LLM participants could leverage tools more strategically, resulting in stronger performance and more cohesive neural signatures

What then?

As I said before, the MIT study comes to a rather obvious conclusion. If we don’t really use our brains to write an essay, we won’t learn much, and that means we might not practice our critical thinking skills. That’s as obvious as saying that if we go to the gym but don’t do the workout, we won’t get fit. Nothing and no one can do the workout for us. We must suffer a little so that the body produces the results we desire. However, if we do put in the work, new tech tools can enhance the results. CAN or MIGHT enhance the results.

I understand the whole “it’s-how-we-use-the-tool” argument. Trust me, I do. In fact, I used ChatGPT to help me proofread and edit this post (and even the image at the beginning). What really worries me is how we’ll be able, as a society, as educators, to encourage people to actually use their brains more and reduce cognitive offloading. What will stop teenagers from generating their essays with AI if it’s widely available and easily accessible (not to everyone, I must say)? Some people say we’ll have to think of more creative ways to assign homework or go back to writing by hand, even banning AI from university libraries.

We are truly faced with an enormous challenge. At the same time we have access to never-before-seen amounts of knowledge, we’re becoming more cognitively lazy to the point where we cannot even take the time to read an entire paper (as long as it may be). Just like readily available processed foods and more options in terms of public transportation have impacted our current levels of obesity and related diseases, how can we make sure that people will actually use their brains in an era of easy access to generative AI? How can we prevent "cognitive sedentarism"?

I do hope we don’t become cognitively sedentary zombies who can’t think for ourselves. But for that to happen, the next time a student says, “Can I just ask ChatGPT to do this for me?” maybe the right answer is: “You can, but first, show me your own thinking. Start with your brain!”

I suppose Eslen’s idea makes perfect sense. We need to reserve some time to be away from the neat and seductive power of AI to get some “brain workout” (do not confuse this with “brain gym”). Because at the end of the day, no algorithm can replace the messy, beautiful, natural, organic, and utterly irreplaceable complexity of the human brain. If every work of art in the future is created by AI, there will be no more Van Goghs. And that would mean that if all systems should fail, we’d have to start creating and recording the knowledge, as well as honing the skills, that generation after generation culminated in the state of the art which made the existence of our beloved Dutch master possible.

So, by all means, use your brain often. After all, as the old neuroscience saying goes:

Use it or lose it

References

Fernando, C., Osindero, S. and Banarse, D. (2024) The origin and function of external representations, Adaptive Behavior, 32(6). 10.1177/10597123241262534

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y. T., Situ, J., Liao, X. H., Beresnitzky, A. V., ... & Maes, P. (2025). Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.08872.

Oakley, Barbara and Johnston, Michael and Chen, Kenzen and Jung, Eulho and Sejnowski, Terrence, The Memory Paradox: Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI (May 11, 2025). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5250447 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5250447