Repetition and Learning: A Lesson from Karate Kid

Students, and often teachers, may regard repetitive tasks as boring and ineffective when it comes to learning. However, who told you that learning needs to be fun all the time for it to work?

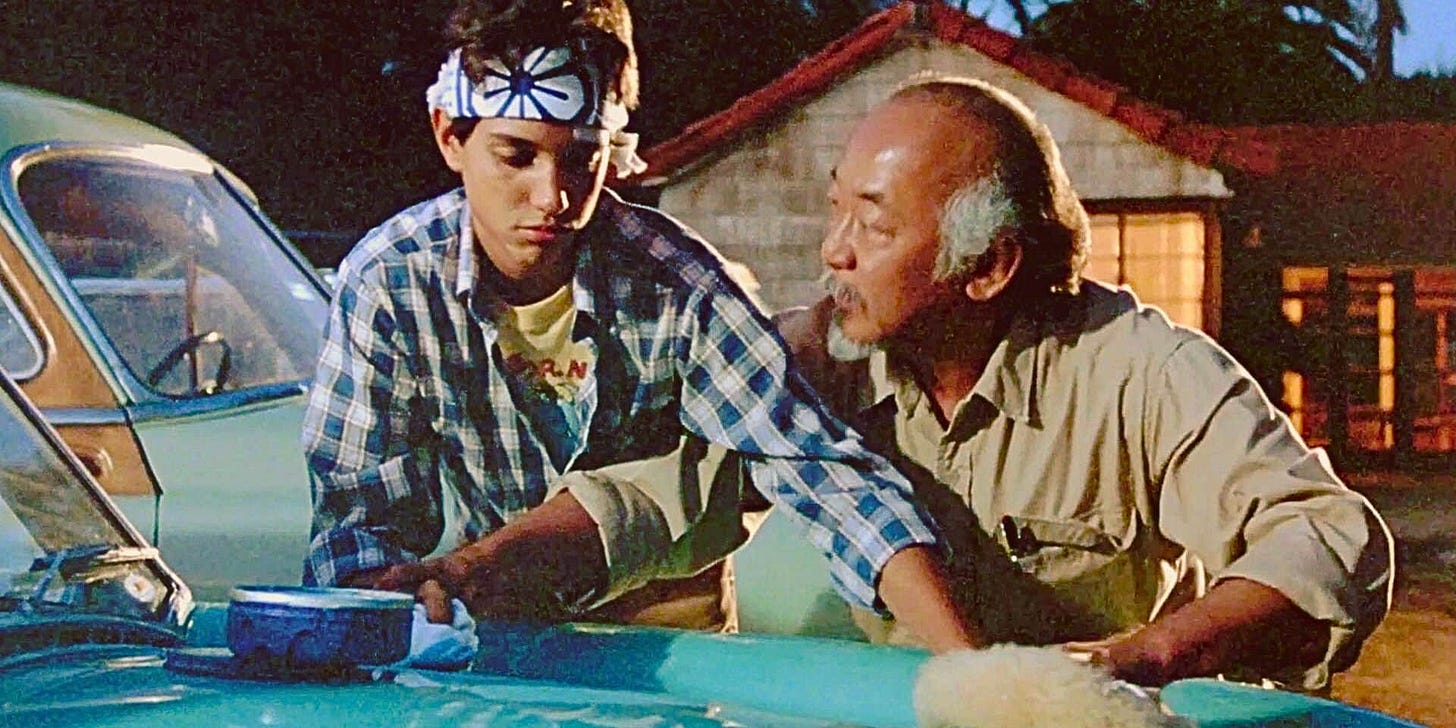

One of my favorite movie characters was a teenager who was bullied at school and on the streets. Recently, I had the pleasure of seeing him again in Cobra Kai, a spin-off of the popular Karate Kid saga. At the time, the movies had a huge impact on many people because they told the story of Daniel LaRusso, a poor kid who was beaten up by a group of bullies led by Johnny Lawrence - until he was saved by the janitor, who happened to be a war hero and Karate fighter born in Okinawa, Japan: the legendary Nariyoshi Miyagi. Mr. Miyagi became Daniel’s Karate master (or sensei) and taught him the essence of this martial art.

All Daniel-san wanted from his sensei was to learn Karate so he could stand up to those bullies. But instead of teaching Karate right away, Mr. Miyagi gave Daniel a series of chores that made it seem like he was just exploiting the poor kid. Daniel had to sand the wooden floor, paint Mr. Miyagi’s house, varnish the fence, and, perhaps most iconic of all, wax the entire collection of cars, including the yellow 1947 Ford Super Deluxe. It was great to see that the Cobra Kai series embraced Daniel’s love of cars and turned him into a successful car dealership owner.

My favorite scene in the first movie is when Daniel-san gets angry and frustrated with Mr. Miyagi’s endless chores. They’re standing in what would later become the Miyagi-Do Karate dojo, run by Daniel himself in Cobra Kai. Daniel doesn’t understand why he needs to wax, paint, and sand, or how that’s going to help him with Karate. Mr. Miyagi then asks him to show the “wax on/wax off” movement. You can see it in Daniel’s eyes the moment it all makes sense as he realizes all that work was meant to build what many call muscle memory and sharpen his reflexes. In that scene, he blocks his sensei’s punches and kicks using the movements he learned through those chores.

There are many lessons in the Karate Kid saga. Perhaps the most valuable one is the idea of focus, commitment, and above all, the role of repetition. Daniel became proficient in the martial art through repetition. Repetition is essential when we want things to become more automatic and thus require less conscious effort. This so-called muscle memory can be developed through a series of intentional repetitions to master what we’re trying to learn. However, we must be careful with a few points. First, we shouldn’t actually call it muscle memory. Memories are stored in networks of neurons in our brain, not in the muscles. Second, the type of repetition, its duration, and its purpose are crucial for developing the skills we aim for.

The Importance of Repetition

Barbara Oakley, Michael Johnston, Ken-Zen Chen, Eulho Jung, and Terrence Sejnowski suggest in their most recent paper The Memory Paradox: Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI that:

At the heart of effective learning are our brain's dual memory systems: one for explicit facts and concepts we consciously recall (declarative memory), and another for skills and routines that become second nature (procedural memory). Building genuine expertise often involves moving knowledge from the declarative system to the procedural system—practicing a fact or skill until it embeds deeply in the subconscious circuits that support intuition and fluent thinking. This is why a chess master can instantly recognize strategic patterns, or a novelist effortlessly deploy a rich vocabulary—countless hours of internalizing information have reshaped their neural networks

Put simply, we can say that repeating tasks makes them require less activation from the frontal areas of the brain, where we find the working memory system. For instance, the first time you try to drive, you need to consciously think through each step in a logical and sequential way. In your mind, you’re thinking:

Okay, first I need to adjust the mirrors and my seat. Now I have to insert the key and start the car. But don’t forget to check if the car is in neutral. Next, I need to put it in first gear and gently release the clutch… oh, and I have to fasten my seatbelt.

Naturally, there are many other steps involved. But imagine how ineffective drivers would be if they had to consciously go through all these steps every time they hit the road! If that were the case, we wouldn’t be able to talk to someone in the car, pay attention to music, or even make a phone call - connected via Bluetooth, of course, to avoid accidents. That’s why our brains create schemas for these tasks, turning them into habits and moving them further back in the cortex, specifically to the parietal lobe - though other areas like the cerebellum are also involved. Habit formation frees up our working memory to do other things.

Even at the cellular level, repetition plays a fundamental role in the learning process and memory consolidation. It serves as a key mechanism to embed information in our brains, making it more accessible and long-lasting through a neurological process called long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP refers to the persistent strengthening of synapses - the areas where neurons connect - when they are frequently activated together. This strengthening results in optimized signal transmission between neurons, which in turn facilitates the more efficient and reliable retrieval of information over extended periods. Essentially, through repetition and LTP, our brains become “finely tuned instruments” for retaining and retrieving knowledge.

Now, imagine for a moment what would have happened to Daniel if he hadn’t internalized all those movements before his famous fight against Johnny at the All Valley Karate Tournament. What if he had to consciously think about each move while those fighters were throwing kicks and punches at him? Well, let’s just say he wouldn’t have made it very far, and we wouldn’t have seen the famous crane kick that earned him the trophy.

Drilling

New concepts and manual skills rely on the same repetition process. In other words, whether I’m learning a new tennis move or new words in English, I need to train, or repeat, to consolidate it into long-term memory.

In English language teaching, we use the term drilling to refer to the repetitions we do during practice. If we think about our English lessons, there are many types of drilling we can use. The idea is to reinforce grammar structures or even vocabulary by repeating them in different ways. This certainly comes from a more behaviorist approach, particularly the audio-lingual method, but we shouldn’t demonize the practice. We just need to understand that foundational knowledge must be consolidated before we move on to more challenging skills. Here are two examples:

Repetition Drills: Students repeat a grammatical structure or sentence.

Substitution Drills: Students substitute a word or phrase in a given sentence with another appropriate one to practice grammar and vocabulary.

OK, you might be asking: When and how often should we repeat? That’s an important question, but a hard one to answer. I see the value of drilling in the classroom, especially for beginner levels, but I definitely don’t think the whole class should be like that, as the audio-lingual method typically proposes. The “train until exhaustion” philosophy might be a foundation of elite sports and athletic competitions, but not of classroom learning when we think about effective and long-term learning. In my opinion, the philosophy of “work while they sleep, study while they party” has done more harm than good. We need to take care of our mental health, and practicing to exhaustion isn’t the way.

So what should we do?

Instead of overdoing it, I’d say we should follow the idea of spaced repetition and retrieval practice. That means doing the same drill for a whole hour is less effective than doing it a few times, then switching to something else, trying to recall and apply it in a different context, resting, and revisiting it again later (e.g., in another class session).

Looking for Better Retention? Combining the book with Spaced Repetition

Is using a coursebook really the best way to teach or learn? There’s a growing debate in education about whether our heavy reliance on textbooks is helping or hindering student learning. Much of this debate focuses on how the syllabus is put together, if content sequence is based on how we actually learn or if books offer more - or fewer - opportunities…

The Age of Repetition Aversion?

What I often see nowadays is the belief that learning must be easy, fun, and without any “boring” parts, which definitely includes repetition. Many people try to sell the idea that “traditional learning” doesn’t work. So they demonize textbooks, grammar exercises, teacher explanations, etc. However, repetition is absolutely essential if we want to do things more automatically (or on autopilot).

Internalizing chunks of information helps us become more proficient users of an additional language and frees up our limited working memory for new learning. That said, I believe there are better ways than simply repeating things mechanically to the point of exhaustion. If we look at some Science of Learning principles, we’ll realize we can often work smarter rather than harder.

Another lesson I want to leave is that changing something deeply rooted in the brain can be quite challenging. Look at the relationship between Johnny and Daniel in Cobra Kai. After all these years, they still basically hate each other, and their worldviews are somewhat reflected in the type of Karate they learned. The cruel and aggressive sensei John Kreese from Cobra Kai taught kids in the ‘80s to:

Strike first

Strike hard

Show no mercy

Cobra Kai Motto

Mr. Miyagi taught Daniel-san a very different lesson:

Rule #1: Karate is for defense only

Rule #2: First, learn rule #1

Miyagi-Do Philosophy

Training, or repeating, in the wrong way from the beginning, based on certain beliefs, can greatly influence our students’ learning curves and their beliefs about their learning abilities. Repetition is certainly fundamental, but it’s only one part of the learning universe when we’re aiming for positive outcomes. We also need care, empathy, and understanding. Even Johnny and Daniel have started to realize how their relationship can improve and what Karate really means.

I suppose the final message here is: don’t demonize the role of repetition, effort, commitment, and a little struggle in learning. Learning doesn’t always have to be easy and fun, and it will rarely take place immediately after exposure. We need to persist and do the basics over and over again to make progress effectively and sustainably.

That brings me to the question I asked in my last blog post here: how can AI be used to encourage students to actually practice and not to avoid the “boring repetitive tasks”? If you have a good answer, please share your thoughts here.

Outsourcing Thinking: Will AI Atrophy Our Brains?

Learning Cosmos is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.